Zion Take Control Of All Rastas

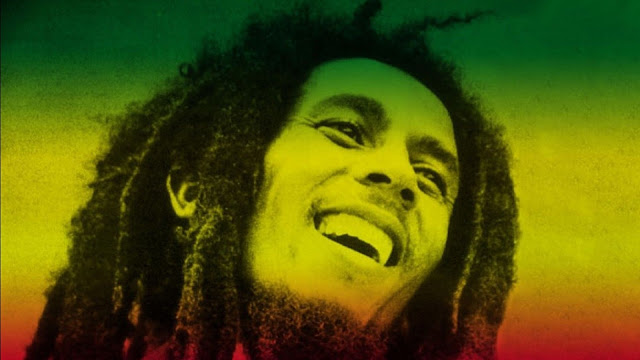

Bob Marley died of cancer on May 11, 1981, at the premature age of thirty-six. By then he was well known to college kids worldwide, but few could have foreseen the celebrity he has attained since. Born in Jamaica, he is the only third-world performer to be elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In 1999, the BBC named his “One Love” the “Song of the Millennium”; the same year Time declared his 1977 Exodus the “Best Album of the Twentieth Century.” Voted the third-greatest songwriter of all time in a 2001 BBC poll (behind Bob Dylan and John Lennon), Marley has sold an estimated 50 million records worldwide. On the 2007 Forbes list of “Top-Earning Dead Celebrities,” he ranked twelfth, with his estate earning an estimated $4 million. His posthumous greatest-hits collection,

Legend (1984), is among the top-selling compilations of all time. Twenty-seven years after his death, there is perhaps no country where his songs—wry ballads and martial anthems, with soothing or stirring melodies—aren’t familiar.

The songs tell a familiar story of black slaves, mainly West Africans brought to work Jamaica’s fields of indigo and sugar cane, combining their own diverse cultures with those they found and making something new. Like many of his contemporaries—young country people who migrated to the city seeking work, only to end up in its swelling slums—Marley absorbed the political and musical currents that flowed through Jamaica and its capital, Kingston, in the years before and after its independence in 1962. Among the sounds were spirituals sung in clapboard churches and folk songs toiled and danced to in fields and shacks; newer rhythms from neighboring islands—mambo from Cuba, calypso from Trinidad; and increasingly, with the advent of the transistor radio and the spread of “sound systems” (turntables and enormous loudspeakers that made musical block parties possible), American doo-wop and rhythm-and-blues.

In a city full of artists and entrepreneurs seeking to forge a new national culture, Marley and his peers—like many others in the third world at the time—adapted these sounds to their lives on the margins. From the early 1960s, Marley became part of the rapid evolution of Jamaican popular music: mento, the calypso-inflected dance style dominant in the 1950s, gave way by the decade’s end to the kinetic hop called ska, and then, in the mid-1960s, to the languid shuffle called rocksteady; finally, a few years later, came the driving, spacious sound of reggae—the style Marley brought to a worldwide audience.

Emerging from the alleyways and harborside recording studios of Kingston in the late 1960s, reggae combined sweet vocal harmonies with an odd new rhythm. Adapting a cadence common to boogie blues, the style’s young artists transformed its characteristic musical feature—offbeat…

Comments

Post a Comment